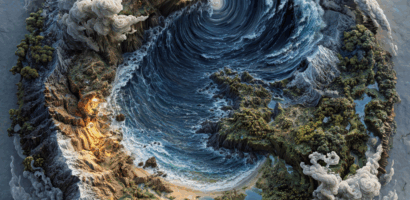

Each year, as we finish reading the Torah and immediately begin again with Bereshit, we are reminded that the study of God’s Word is a never-ending circle. On Simchat Torah, we celebrate this remarkable rhythm: no sooner do we complete the last verses of Devarim than we return joyfully to the first words of Genesis—“Bereshit bara Elohim et hashamayim ve’et ha’aretz,” “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.”

This year, Simchat Torah carried a special, almost indescribable emotion. After two years of sorrow and anxiety, Israel finally rejoiced again—rejoiced not only in the Torah, but in the homecoming of hostages. It felt as though the circle of life and faith had reopened: out of darkness came light, out of captivity came freedom. And so, as we start reading Bereshit again, the story of creation feels especially real to us—a reminder that God’s creative power still brings order out of chaos, light out of darkness, and hope out of despair.

This renewal is not merely a liturgical tradition. It expresses a deep spiritual truth: that each reading, each return to the beginning, opens new meanings. The text remains the same, yet our lives, our world, and our understanding have changed. To begin Bereshit again is to begin ourselves anew—to see creation once more through the eyes of faith and wonder, and to rediscover what God’s design means for us today.

The Book of Beginnings

The Hebrew title of Genesis, Bereshit, comes from its very first word. It is a book of beginnings—of the world, of humankind, of Israel, and of God’s covenantal relationship with creation. The opening verse, “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth,” is among the most recognized lines in all of Scripture. Even those who may not profess faith often know these words, perhaps sensing intuitively that they hold a key to the mystery of existence itself.

I have always felt that this single verse is like a narrow but radiant window into eternity—a glimpse of God’s timeless plan. The word Bereshit—בְּרֵאשִׁית—is small, yet it contains within it the vastness of divine intention. The sages of Israel noticed that the Torah does not begin with Alef, the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, but with Bet, the second. Why does the revelation of God to humankind begin not with the first, but with the second letter?

Why Bereshit Starts with Bet

Rabbinic tradition offers several beautiful answers. One Midrash explains that because the numerical value of Bet is two, the Torah opens with the message of “two worlds”—this present world and the world to come. Another suggests that we are to begin our study not as if we are the first to approach God’s Word (Alef), but as those who join a continuing conversation (Bet), drawing upon the wisdom of those before us.

Yet there is another explanation I find especially meaningful: we are not meant to know everything. The Alef, symbolizing the ultimate beginning, belongs to God alone—“there was no beginning to His beginning.” The Bet of Bereshit marks the boundary between the hidden and the revealed, between “the secret things that belong to the Lord” and “the things which are revealed” that belong to us, that we may do His will (Deuteronomy 29:29).

In many Torah scrolls, the Bet of Bereshit is written slightly larger than the surrounding letters. Although Hebrew has no capital letters, this enlarged Bet visually signifies the opening of revelation—the first visible doorway into divine mystery.

Even the syllables of Bereshit contain meaning. The first two letters—Bet and Resh—form the word bar, which means “son” in Aramaic and also appears in Hebrew words such as Bar Mitzvah. Thus, the first syllable of the entire Bible literally means “son.” For those who believe in the divine Son, this is a remarkable hint woven into the very opening of Scripture: the revelation of God begins with the word Son.

Spirit or Wind?

When we read the Christian Bible in English, we encounter God’s Spirit at the very beginning of creation: the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters, says Genesis 1:2. However, in many Jewish translations of Torah, the same verse speaks about the wind of God sweeping over the water. Which translation would be correct? You may already know that ruach in Hebrew means both wind and spirit, but how do we distinguish between the two meanings? How do we know what the text means? Is it God’s Spirit that hovers over the primordial waters, or just a wind that sweeps over these waters?

We find an answer through the verb that follows the word ruach: merahefet. Remarkably, this verb occurs only once more in Torah—at its very end, in the song of Moses in Deuteronomy 32: the love of God to Israel is being likened here to the utmost care, love and affection of an eagle fluttering (yirahef) over the young ones and bearing them upon its wings.

He kept him as the apple of His eye.

As an eagle stirs up its nest,

Hovers over its young,

Spreading out its wings, taking them up… [1]

Whilst there is a certain similarity between spirit and wind (which is why in the NT Yeshua compares them), there is also a very profound difference: wind cannot express tender love, care and affection! A wind blows dispassionately and indifferently, while the Spirit of God caringly and lovingly hovers over His creation. This loving, personal, passionate hovering that we see in Deuteronomy 32:11 and Genesis 1:2 can only pertain to God’s Spirit—not to the wind! Thus, through this one word alone, we can catch a glimpse of the amazing depth of the original Hebrew text.

The Creative Word: VaYomer

As we proceed through the verses of Bereshit, we encounter a series of verbs describing God’s creative acts. The first and most prominent of them is VaYomer—“and He said.”

Nine times in the creation narrative we read, “And God said …” (VaYomer Elohim). Each time, what He says immediately comes to be: “Let there be light.”—and there was light. In our present world, we live by faith and not by sight. We trust that what God has spoken will come to pass, but we rarely see that instantaneous correspondence between word and fulfillment. In the pristine world of Genesis 1, however, this immediate embodiment of God’s Word was not a miracle—it was the natural order. Creation responded instantly to the voice of its Maker.

This verb VaYomer thus teaches us two foundational truths. First, that God alone possesses life-giving power. Second, that this power is exercised through His Word. The davar Elohim—the word of God—is not merely sound but substance; it carries the creative authority of life itself.

It is no wonder that the opening of John’s Gospel deliberately echoes Genesis: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. … All things were made through Him.” The same creative Word that brings forth life in Genesis is revealed in the New Testament as the life-giving Logos, the eternal Son. The author of Hebrews affirms: “By faith we understand that the worlds were framed by the word of God.” (Hebrews 11:3)

The contrast between divine and human power is striking. When the prophet Elisha raised a dead child (2 Kings 4:32-36), he prayed, stretched himself upon the body, prayed again, and finally the child revived. Jesus, by contrast, restored life exactly as God created it—by the Word alone: “Talitha kumi!” “Lazarus, come forth!” “Young man, I say to you, arise!” The Gospels portray His spoken Word with the same life-creating power that we first encounter in Genesis.

The Work of Separation: VaYavdel

A second recurring verb in the creation story is VaYavdel—“and He separated.” “And God saw the light, that it was good; and God separated the light from the darkness.”

During the first three days of creation, this act of separation (lehavdil) dominates God’s work. He separates light from darkness, the waters above from the waters below, and dry land from the seas. Only after this threefold separation does the earth begin to yield fruit.

This pattern teaches a profound spiritual principle. Before fruitfulness can come, separation must occur. Just as God divided light from darkness in creation, He calls each of us to distinguish between what belongs to Him and what does not. The Hebrew root havdalah—known from the ceremony that marks the end of Shabbat—means precisely this: to make distinction, to set apart. The ability to discern and separate is the foundation of holiness. Only when the boundaries are established—when light is chosen over darkness—can true growth begin.

Naming: VaYikra

Another verb central to the creative process is VaYikra—“and He called.” “God called the light Day, and the darkness He called Night.” (Genesis 1:5) “God called the firmament Heaven.” (1:8) “God called the dry land Earth, and the gathering of the waters He called Seas.” (1:10)

To call or to name in the biblical sense is not merely to label; it is to define essence and purpose. By naming the elements of creation, God establishes their identity within His order. Speech, again, becomes the instrument of creation and meaning.

It is therefore deeply significant that the first human act recorded after man’s formation is also VaYikra—naming. Adam gives names to every creature (Genesis 2:19-20). In doing so, he participates in God’s own creative work, exercising the same faculty of meaningful speech that reflects the image of the Creator. Naming implies both authority and relationship; to name something rightly is to recognize its place within God’s design.

Beginning Again

Every year, as we return to Bereshit, we are invited to begin again—to look through the same letters and see deeper light. The Torah’s circle of reading mirrors the cycle of creation itself: each new beginning builds upon what came before. Just as the Bet of Bereshit signifies continuity rather than absolute beginning, so our study is not a first encounter but a renewal of understanding.

To start Bereshit again after Simchat Torah is to affirm that Go d’s Word remains alive, still speaking, still creating. In the same way that His first words brought light into darkness, His Word continues to bring light into our own hearts and our world. And so we begin again—not from Alef, but from Bet—not as those who know nothing, but as those who have seen much and yet long to learn more.

If you like the insights on this blog, you might enjoy my book “Unlocking the Scriptures”, you can find it here: books. And, as always, I would be happy to provide more information (and also a teacher’s discount for new students) regarding our wonderful courses (juliab@eteachergroup.com)