Zman simchateynu—“the season of our joy”

In Israel, we have just finished celebrating Sukkot—the Feast of Tabernacles. The streets of Jerusalem were filled with pilgrims, families gathered in their sukkot decorated with fruits and lights, and prayers for rain rose up from every congregation. As always, there was a sense of joy, renewal, and anticipation that comes with this feast.

This year, however, the joy was especially deep. On the very last day of Sukkot, Israel rejoiced in the miraculous return of some of the hostages. The festival is called zman simchateynu—“the season of our joy”—and this time the words felt tangible, alive, filled with tears and gratitude. The collective joy of a nation welcoming its sons home gave us a glimpse of the kind of restoration and hope that Sukkot has always pointed to.

It is in the afterglow of these celebrations that I want to take you back almost two thousand years, to the time of Jesus, and explore how this festival was kept then, and how it reveals the mystery of Messiah’s coming. How did the Jews celebrate Sukkot in the time of Jesus? What did this feast mean for Him personally—and could it even have been the time of His birth? Today, I want to explore the Feast of Tabernacles, both in the way it was observed two thousand years ago and in the way it illuminates the story of Jesus. Along the way, we will discover how the joy of Sukkot, the rituals of water and light, and the promise of God’s presence all come together in Him.

The Water and the Light

In John 7 we hear the famous words of Jesus: “Out of his heart will flow rivers of living water.” For centuries, Christians have understood these words primarily as a metaphor for the Spirit. Yet, when we remember that Jesus spoke them during Sukkot, their meaning becomes even richer.

If you have ever been in Israel during Sukkot, you know how central water is at this season. From Passover to Sukkot, the land receives no rain. By the end of the summer, the fields are brown, the ground is dry, and all creation longs for the first showers. Sukkot marks the turning of the year, the beginning of the rainy season, and the prayers in the Amidah change accordingly: in summer, “He causes the dew to fall”; in winter, “He makes the wind blow and the rain fall.” God’s clock is precise, and almost every year, the first rain arrives just after Sukkot.

It was the same in the time of Jesus. In the days of the Second Temple, the highlight of the festival was the water libation ceremony. A golden pitcher of water, drawn by a priest, was carried in a joyful procession from the Pool of Siloam to the Temple. There, with great rejoicing, the water was poured upon the altar. Though not commanded in Torah, the ceremony was rooted in Isaiah’s promise: “You shall draw forth water with gladness” (Isaiah 12:3). The rabbis taught that on Sukkot the world was judged concerning rainfall, so Israel prayed for God’s blessing in the year ahead.

Imagine the scene: throngs of worshipers, the courts of the Temple alive with music, the lamps blazing with light that could be seen throughout Jerusalem. It was in this setting—when water was carried in procession and lamps shone over the city—that Jesus declared, “If anyone thirsts, let him come to Me and drink.” And again, “I am the light of the world.”

Once we place His words in their historical context, they become even more powerful. Jesus was not speaking abstractly. He was standing in the midst of Israel’s greatest festival of water and light, declaring Himself to be the true source of both.

The Honorable Guest

But did Jesus Himself celebrate Sukkot? Scripture says He did. John 7 tells us that when His brothers urged Him to go up to the feast, He replied, “My time has not yet come.” Later, however, He went up quietly, “not openly, but as it were in secret.”

Why the secrecy? On one level, this reflects the mystery of the Hidden Messiah. His brothers essentially challenged Him: “Show yourself to the world!” But Jesus answered that His time had not yet come. He was not yet ready to reveal His identity fully.

On another level, secrecy may have had something to do with hospitality. One of the special mitzvot of Sukkot is to invite guests into one’s sukkah. The sukkah is often seen as echoing the tent of Abraham, the first to welcome strangers with open arms (Genesis 18). On the first night especially, it was considered a great honor to host guests. As a rabbi, Jesus would have received many invitations, and traveling quietly may have allowed Him to accept one particular invitation close to His heart.

So He went up to Jerusalem, quietly yet purposefully, to celebrate Sukkot—the feast of joy, fellowship, and divine presence.

“Let Us Make Tabernacles”

Sukkot also echoes in another moment of the Gospels: the Transfiguration. On the mountain, Jesus’ appearance changed—His face shining like the sun, His clothes dazzling white—as He spoke with Moses and Elijah. Witnessing this glory, Peter exclaimed, “Lord, it is good for us to be here. If You wish, let us make three tabernacles: one for You, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.”

At first, Peter’s suggestion seems odd. But in light of Jewish tradition, it makes sense. The sukkah was not only a reminder of Israel’s wilderness huts—it was also understood as a dwelling overshadowed by the Divine Clouds of Glory. To build a sukkah was to acknowledge God’s presence among His people. Peter, seeing the radiant glory of Jesus, instinctively reached for the symbol of Sukkot: a booth covered with God’s glory.

Details like this remind us how deeply the Gospels are rooted in first-century Judaism. Without that context, we miss the depth of what the apostles saw and experienced.

When Was the Silent Night?

This brings us to another question: could it be that Jesus was born at Sukkot? The Gospels never specify the time of His birth. The December 25 date was established much later, centuries after the first believers, and does not arise from Scripture. In fact, many clues suggest that late summer or early fall is more likely.

First, the shepherds. Luke tells us they were in the fields, keeping watch over their flocks at night. That would not happen in December, when nights in Judea are cold and wet. By contrast, early fall is the perfect season for shepherds to be outdoors with their flocks.

Second, the census. Roman censuses were unlikely to be scheduled in winter, when travel was difficult due to cold and rain. Early fall, coinciding with the great pilgrimage feast of Sukkot, would have been much more practical. Joseph and Mary may even have joined a caravan of pilgrims traveling south, which would also explain the overcrowding in Bethlehem.

Third, the timeline of John the Baptist. Luke carefully notes that Zechariah, John’s father, served in the priestly division of Abijah. From 1 Chronicles 24, we know when that division ministered in the Temple. Calculations suggest that John was conceived in early summer and born in late spring. Jesus, conceived six months later, would then have been born in early fall—around the time of Sukkot.

Theological Reasons

But beyond historical clues, there are profound theological reasons to connect Jesus’ birth with Sukkot.

- The Feast of Joy. Sukkot is called zman simchateynu—“the season of our joy.” What more fitting time could there be for the angel to announce “good news of great joy for all the people”?

- Tabernacling among us. John writes: “The Word became flesh and tabernacled among us.” His choice of words seems intentional, pointing to the Feast of Tabernacles as the moment when God literally came to dwell with His people.

- A light to the nations. Sukkot was always meant to draw the nations to worship the God of Israel. Zechariah prophesied that in the end of days, all nations will go up to Jerusalem to celebrate the feast. Is it not fitting that the One who came as a light to the nations should be born at this feast?

- The Temple connection. Solomon dedicated the First Temple at Sukkot. If the earthly temple was inaugurated then, how appropriate for the true Temple—God dwelling in human flesh—to be inaugurated at the same time.

- The return of God’s presence. After the golden calf, Israel received the second set of tablets on Yom Kippur, but it was only at Sukkot that God’s glory returned to dwell among them. Sukkot celebrates God’s presence restored to His people. What more fitting time for Emmanuel—God with us—to be born?

Emmanuel—God With Us

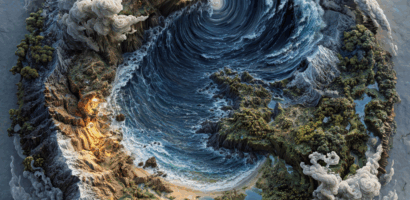

Whether we consider Jesus standing in the Temple and proclaiming Himself as living water and light, or whether we imagine His birth in a humble shelter during Sukkot, the themes converge: God dwelling with His people.

Sukkot is about joy, water, light, presence, and fellowship. It is about remembering that we are not orphans in this world. And it is about anticipating the time when all nations will come to Jerusalem to worship the King.

When we see Jesus in the light of Sukkot, His words and actions become even more profound. He is the water that quenches thirst, the light that pierces darkness, the hidden guest who comes quietly yet transforms every dwelling into a place of glory. He is the one who tabernacles among us, and in Him, the broken are healed, the exiled are gathered, and the presence of God fills the earth once more.

Immanu El. God with us.